A Twitter image archive is being used to spread fake news with a PBS label. This investigation shows how even honest mistakes feed division among news consumers in America.

A media study recently put Public Broadcasting Service near the top of the trustworthiness pyramid.

OK, that’s old news. PBS routinely does well on such surveys, underscoring the service’s drive to be the straightest talker in a public affairs landscape increasingly inhabited by decidedly partisan news (and let’s face it, entertainment) sources.

And there’s an important new study from the Gallup Organization and the Knight Foundation’s “Trust, Media and Democracy” series that looks more deeply into why audiences and readers are losing confidence in the news media.

I know. You’re squinting your eyes at me right now. You’re wondering why I’m crowing about PBS being on top of a trustworthiness pyramid that is crumbling.

My answer involves a concern about an increase in bogus, yet very visible, “news” sites on the Internet. I believe social media is to blame.

Yes, social media is now an indispensable part of our lives. For many, it’s the source of news, while it allows us to stay close to friends and family spread far and wide. But social media can also lead us into traps of phonied-up “news” and propaganda that we then recycle in our online circles.

The trust measure I cite at the top of this column is the Brand Keys survey, which for 2019 says the BBC is the most-trusted news site. PBS is number three on that list.

What’s surprising is that the survey found Fox News and MSNBC — the most partisan of news sources, each on its own pole — are numbers two and four on the list, respectively.

This confirms for me that we’re living in what the kids on Netflix’s “Stranger Things” series call The Upside Down. We Americans no longer agree on anything, even the basic facts we need to have an honest and productive discussion. Every side in a political debate now says the facts the others use are fake and trust only the facts that reinforce their particular political beliefs.

That’s revealed in the Gallup-Knight survey, which claims that most people believe the “other side” spews fake news:

“A majority of Americans currently see "a great deal" (49%) or "a fair amount" (37%) of political bias in news coverage -- more so than in 2017. Although 56% of U.S. adults see at least a fair amount of bias in their go-to news source, they are much more concerned about bias in the news other people are getting (69%) than about their own news being biased (29%).”

PBS, for its part, remains committed to quality journalism, the core of its public media mission.

That means defining and consistently applying standards, said PBS CEO Paula Kerger, when we asked her to comment on where PBS stands today in a splintered news environment:

“The importance of trusted news has never been more important than it is today. Amid rampant misinformation and constant attempts to distort the truth, there is an urgent need for the kind of serious journalism that is central to the mission of public television. Together with our producing partners and local stations, PBS delivers journalism that adheres to the highest standards of editorial integrity – whether through a nightly news program such as ‘PBS NewsHour,’ or an 18-hour documentary like ‘The Vietnam War.’ We are fortunate to work with extraordinary journalists who get at the heart of the truth and speak truth to power. As the tools and platforms evolve, we will uphold our editorial standards, and we will continue to inform and engage the American public in the pressing issues of the day.”

Not Really PBS

This all matters because an informed public that understands how news is gathered -- and trusts honest media organizations -- is essential to a functioning democracy.

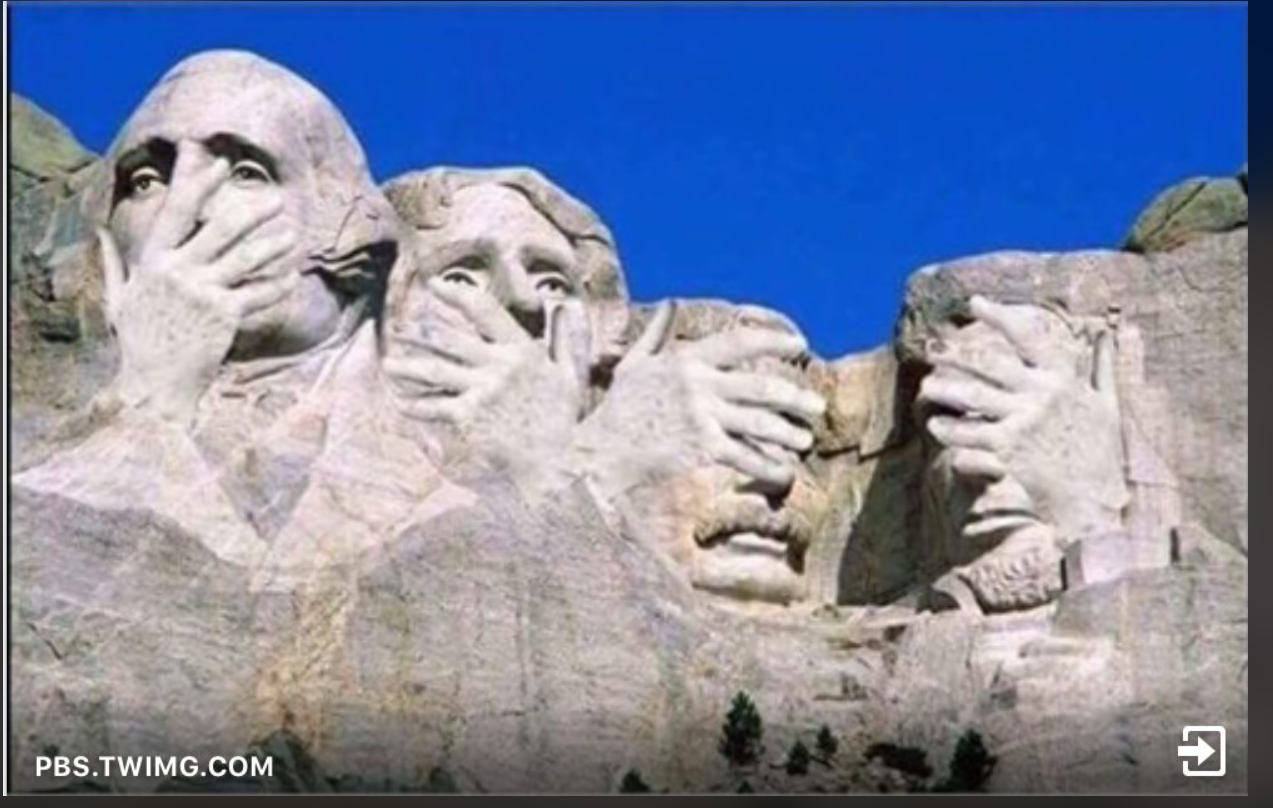

This is why, for months, a “news” source has been bothering me. It’s a font of bogus information that some PBS viewers have used to circulate fake news. Even some of my friends and family have reposted items gleaned from something called PBS.Twimg.com.

You know who you are. I invite you now to stop. The material is dangerous. Not only is it fake or sensationalized news that you’re sharing, but it may be spreading computer malware or viruses.

Moreover, it ain’t PBS. The real PBS.org has never posted things like a photo of President Donald Trump under lettering that says, “Excuse Me, I’m Trying To Lie Here.”

Yet the familiar-sounding web address continually fools viewers into thinking that it’s us, the trusted news source, sending out such messaging.

Some in our audience have become concerned enough to ask us if PBS was really endorsing some outlandish statements.

The most recent alert came from a person, who recently and rather innocently asked for our help in obtaining permission from PBS to repost an image that encouraged mask-wearing during the pandemic. This one seemed well-intentioned, but its source is an X factor and the encounter illustrates how easy it is to misconstrue the source of a given piece of information.

We told the inquiring person that no such permission was possible because the real PBS has nothing to do with PBS.Twimg.com.

Here are two more, emblematic inquiries we have received from viewers confused by PBS.Twimg.com:

“Can someone please help me, I was told by a Facebook friend that your Website shows President Trump claim that he donated his 3rd quarter salary. If so please help me to find this article on the website PBS.org. I'll thank-you in advance for the help.”— Mark, a local Detroit Public TV viewer

“There are inflammatory and contradictory FB posts under PBS.TWIMG.COM. ONE posts the name and images of someone alleged to be The (Trump-Ukraine) Whistleblower. Just after I got that one, I got a post that is anti-Trump. I reported the Whistleblower post to FB.” — Nancy Basinger, Dallas, Tex.

Acronym hell

Researcher Dan Macy and I found out that this source of fake news has a complicated back story. But that it exists, and that people easily mistake it for the real PBS, says something about where we are today as a society: We thrive on confirmation bias and call it “news” when it suits our beliefs. We expend little if any effort verifying authenticity.

After receiving several complaints from viewers about biased PBS material circulating on social media, we set out to see who or what was behind PBS.Twimg.com.

With the help of data experts and PBS’ IT department, we were told the address is hosted by a web domain registry in Reston, Virginia. So we contacted the registry, VeriSign Global Registry Services, and were referred to another company called CSC Corporate Domains, Inc.

VeriSign, in an online chat, acknowledged “we are the registry operator for the .COM TLD, meaning we manage the master file but the domain is not registered with us.”

Confused? So were we. We called CSC and were referred to Twitter, whom we then began pelting with requests for comment, via ….er, Twitter, and old-school methods like emailing and calling on the phone, in search of Twitter’s corporate communications minders.

After a second email, a Twitter employee named Liz Kelley surfaced briefly, with the following email message: “Hi Dan - apologies. I'm not sure how your initial email was lost. Looking into this for you.”

After several weeks passed we sent another email to Ms. Kelley to follow up — this time to her direct email address at Twitter — but she did not reply.

The PBS.Twimg origin story

How the web address became a fake-news bazaar remains a mystery. If you put PBS.Twimg.com into a web search, you get a mixed bag -- political images in some cases, or error messages in others.

New Jersey-based journalist and data researcher Jorge Melchor helped us track the origins of PBS.Twimg.com. He found suspicious sites with no single owner.

“There’s nothing there except bad links and they could be adding malware to your computer,” Melchor said.

Still, PBS.Twimg.com material seems to be everywhere, but coming from nowhere.

One of our earnest tech wizards then discovered a possible, more innocuous origin story for PBS.Twimg.com, and explains why audiences might confuse it with the Public Broadcasting Service:

The PBS part of the suspicious address is actually a clumsy acronym.

At Twitter there is something called the “Photo Blobstore,” a service Twitter uses to archive millions of images that cross its social platform. The Blobstore was set up to isolate not just "bad" files, but all image files that accompany tweets. Meanwhile, “Twimg” stands for “Twitter imaging” and is used to sequester photos and graphics determined to come from suspicious sources.

Here’s what a helpful article, provided by Twitter in 2012, says about the Blobstore. Our IT specialist found this during his deep dive into the subject:

"When a user tweets a photo, we send the photo off to one of a set of Blobstore front-end servers. The front-end understands where a given photo needs to be written, and forwards it on to the servers responsible for actually storing the data. These storage servers, which we call storage nodes, write the photo to a disk and then inform a Metadata store that the image has been written and instruct it to record the information required to retrieve the photo .... The Metadata store...spans across all of Twitter's data centers providing a consistent view of the data that is in Blobstore."

Data researcher Jorge Melchor added that Twitter tries to isolate potentially harmful material that comes onto the platform:

“The files are isolated by Twitter, and they have the safe link http://t.co. But somehow (fake news producers) use this isolation to instead reproduce a PBS link. It’s malware for sure."

Our PBS tech team decided to write and post a FAQ (frequently asked questions) on the subject, which you can read here. Check back periodically, because as we learn more we’ll add to this document.

A possible solution

The World Wide Web is a complex universe, bountiful with unintended consequences.

It might not seem like a big deal. PBS has seen no obvious damage of late to its news and public affairs reputation because of the bogus “news” source. But on social media, lies and slants and even innocent mistakes, spread like a California brush fire.

In the case of PBS.Twimg.com, there is one easy way to stop its spread:

Two media giants, PBS and Twitter, should sit down and talk.

In these pandemic days, a meeting means facing each other via Zoom or Microsoft Teams screens. Twitter needs to know that it has created a monstrous fake news source. It probably didn’t mean to do so, yet it’s out there and it’s proving a hard beast to kill.

That could take care of one of today’s less pernicious forms of disinformation. But it will show that with cross-media cooperation, we can tackle intentional disinformation.

The ongoing PBS.Twimg.com confusion is a microcosm of the larger disinformation storm around us. It’s also a starting point to plot how traditional media and social media can cooperate to disentangle complications that seem inevitable in an open information universe.

If anyone knows the value of a trusted brand it’s the people at PBS. Those three letters are so trusted that their appearance together, in order, in a simple Internet address, is enough to make some people think “Public Broadcasting Service.”

Eliminating PBS.Twimg.com will help the real PBS protect its viewers from the consequences of fake news. Our audience is an engaged lot. PBS viewers love to vote. They merit trusted news sources.

The trust deficit

The PBS.Twimg.com episode reveals a paradox: Media audiences are less trusting of established news outlets, but they’re simultaneously turning more frequently to shadowy sources of a spammy substance parading as “news.”

This leads to another troubling online trend: On social media, dubious items and stories from trusted brand names are often afforded equal weight.

Earlier in this column, you may have noticed where a couple of our viewers said they saw these pieces of counterfeit information. That’s right: Facebook.

I am not here to bash a digital media brand that commands an expansive empire. But in a July congressional hearing, Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) adroitly highlighted a unique and troubling incident that demonstrates Facebook’s role in the undermining of American journalism and its CEO was disconcertingly nonplussed in his response.

Asked Rep. Nadler of Mr. Zuckerberg:

“In 2015, Facebook reported high and quickly growing rates of video viewership on its platform. Based on these metrics, publishers fired hundreds of journalists choosing instead to boost their video divisions. In 2018, it was discovered that Facebook had inflated these metrics, but had known about the inaccuracies several years before. Did you know these metrics were inflated before they were publicly released?”

By some accounts, Facebook overstated the metric by 900%.

Zuckerberg said “No.”

“ … We regret that mistake and we have put in place measures since that time.”

To another subcommittee member, a Republican who questioned Zuckerberg about his company’s methods of handling false or misleading information, the digital wunderkind had this to say after explaining that the company works with 70 fact-checking “partners” around the world: “We don’t ourselves want to be in the business of determining what is true and what is false.

“That feels like an inappropriate role for us to play,” added the CEO of the corporation that rakes in $70 billion yearly in advertising revenue.

You would think an executive with so much money on the line would want to take a bigger stake in what’s true and what isn’t. Can you imagine the head of a national television network disavowing any role in deciphering truth from falsehood?

Until social media titans wake up and see the urgency of ensuring the quality of the olio they’re allowing to be mixed online, we will continue to do our part and provide a forum for PBS viewers to call out fake news when they believe they see it.

---

PBS Public Editor Researcher Dan Macy contributed to this article.